To Infinity & Beyond!!

Kerr Financial Group

Kildare Asset Mgt.

Jeffrey J. Kerr, CFA

Newsletter

September 23, 2019 – DJIA = 26,935 – S&P 500 = 2,992 – Nasdaq = 8,117

To Infinity and Beyond!!

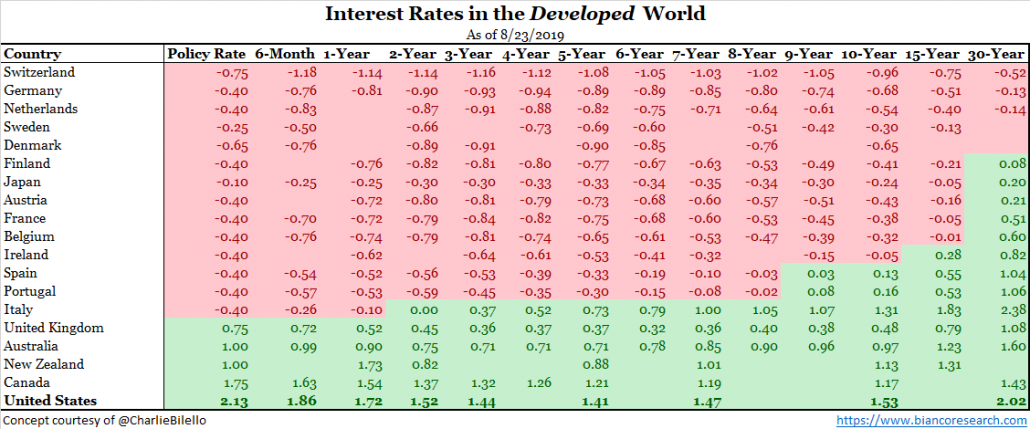

Ten years ago, central banks slashed interest rates in an effort to stabilize the global economy from the financial crisis. Since reducing interest rates had worked in prior recessions, it was the “go to” strategy and considered the proper move. We were confidently assured that this was temporary, and rates would be back to normal in a jiffy. Yet, for the past decade, despite forecasts of rates returning to historically normal levels, it has been a path of steadily lower interest rates.

In addition to cutting interest rates, the world’s monetary leaders included additional strategies to combat the downturn. On top of pumping the system with money and reducing interest rates, these bankers implemented aggressive steps such as broad financial bailouts of total industries and key companies. They pulled out all of the stops.

Again, we were told that these radical and untested tactics were necessary and that it would be only short-lived. Ten years later, this transient remedy has become the norm. And like the frog in a pot as the heat is turned up, we have gradually become immune to dangers and risks that the global bureaucrats have shoveled on the system in name of saving it.

Two weeks ago the European Central Bank announced another round of “quantitative easing”. Specifically, the ECB lowered interest rates to an even lower negative level. The short term rate is now set at minus 0.5% for the reserves that banks hold at the ECB. This means that banks will lose approximately €9 billion per year on these funds that they are required to keep at the ECB .

Another important part of the announcement involves a new asset purchase program. The ECB will be buying €20 billion of bonds per month. This was less than the €30 billion that was expected but, to offset the disappointment, this program is open ended or has no set termination. Traders quickly began calling it “QE Infinity”.

In summary, Mario Draghi and the ECB are re-cycling and re-implementing the same policies that haven’t worked despite over 10 years of trying them. It is astonishing that these people have any credibility. Strangely, it seems, that as long as the system doesn’t implode, they are consider competent.

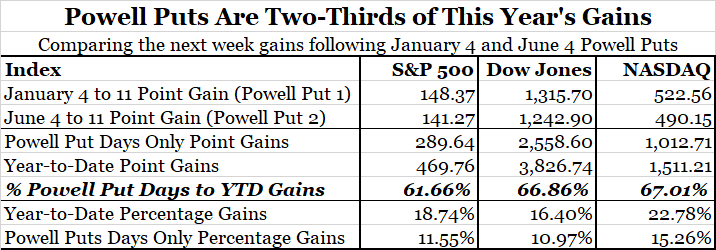

Of course, it’s not much different on this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Last week the Federal Reserve cut its benchmark interest rate one-quarter of 1%. It was the second cut in the past couple of months. There was some dissention concerning the decision to cut as three of the ten members of the committee voted against it. Chairman Powell pointed to a global slowdown and trade tensions as the chief reasons.

While this interest rate decision was broadly expected by the markets, the Fed was involved in some other unexpected developments last week. The banks have a system of borrowing and lending on an overnight basis. This is based on whether a bank has surplus liquidity or a shortfall according to regulatory measurements. The Fed stands as a lender if needed but, historically, banks view them as a last resort and would rather find the liquidity elsewhere.

Last week, for the first time in a decade, the Fed loaned around $200 billion over three days to banks in the form of short term loans. Many were alarmed and questions were raised on the cause of these developments. Mr. Powell downplayed the news and said it had no economic impact or shift in monetary policy. The capital markets will be watching to see if this is a single occurrence or if this becomes an ongoing problem.

The markets have a lot of confidence in the Federal Reserve’s ability. Perhaps too much. The Fed employs hundreds of PhD’s who are paid several billions of dollars annually. They have access to unlimited technology and computer models to assist in their analysis. Yet, despite all of these abilities and tools, they refer to themselves as being data dependent. In other words, instead of having definitive forecasts of future conditions, as is considered their critical role, they react to economic data as it is released. Apparently, advanced academics and the best programming is a lot more fluff than substance.

The U.S. 10-year note’s yield closed last week at 1.75%. This is a little higher than the start of September (around 1.5%) but down from 2.7% in March. It’s a surprising statistic that the 10-year U.S. Treasury note has provided a total return well above 10% so far in 2019. Likewise, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond index (the main U.S. fixed income index that includes all bond sectors) has an approximate total return of 10% in 2019. These are attractive returns for a traditionally less volatile asset class (fixed income).

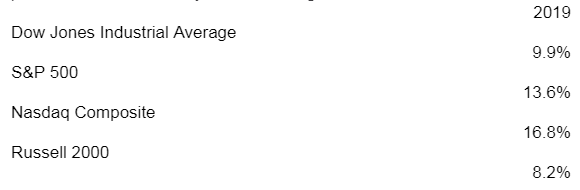

Turning to the stock market, the major indexes slipped around 1% last week. The recent action has been a sell off from record levels in late July and a bounce from mid-August. We remain below July’s highs. Obviously, there are strong economic, social, and political crosscurrents that the markets are digesting. Here are the major indexes year-to-date returns through last Friday.

Contrary to the gains of 2019, the returns for the past 52-weeks (year over year) are much less exciting. The Dow, S&P 500, and Nasdaq are barely positive. The Russell 2000, which may be a closer representation of the average stock, is down almost 9%. As a reminder, 2018’s 4th quarter was one worst in recent years with December being especially bad.

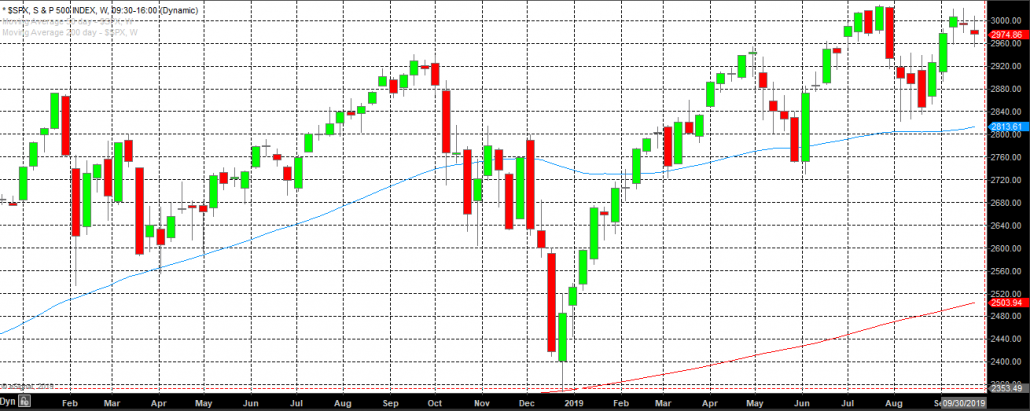

The reality is that stocks have not gained much since the highs in late January 2018. There has been a lot of movement but it’s been a back and forth variety without material progress. This is shown in the chart of the S&P 500. Each bar (candlestick) represents 1 week and the time frame begins in January 2018. The selloffs in February, 2018 and last year’s 4th quarter are clear reminders that stocks have risk.

The future direction of the capital markets will be influenced by interest rates. They are a critical part of the environment and are being controlled global central banks. The following quote from Jim Grant is an accurate painting of the landscape.

Interest rates are probably the most sensitive and consequential prices in capitalism. They balance savings and investment, discount future cash flows, define investment hurdle rates, measure financial risk.

Yet the Fed and its foreign counterparts seek to manipulate, or, at least, to influence, interest rates both long- and short-term. They can’t seem to keep their hand off them.

Wall Street raises no protest against these intrusions. The artificially low rates of the past 10 year have advantaged investors, speculators, and corporate promoters. They have deadened the risk sensors of even professional investors. They are the Jack Daniel’s-grade financial disinhibitors.

The same low rates – by some measure, the lowest in 4,000 years – have penalized savers incentivized dubious risk-taking, expedited the growth in federal indebtedness and perpetuated the lives of businesses that would have ended in the absence of easy credit. They have widened the gulf between rich and poor, thrown a spanner into our politics and inflated the cost of retirement.

The trouble is that the costs of radical monetary policy are dark and prospective; the gifts they bestow are bright and immediate. These gifts are likewise transitory.[i]

During the past 10 years monetary policy has shifted to a higher level of intrusion. Free markets are unarguably less free. So far, the markets have accepted and adjusted to this development. This leads to perhaps the largest risk in the capital markets – a loss of the market’s confidence in central banks and their policies. A confidence crisis is hard to forecast especially since the markets have seemingly approved the current conditions. However, if investors start to doubt monetary leaders, the adjustment could be long and painful.

[i] Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, May 17, 2019